Concrete Embeds

by Giuseppina Forte

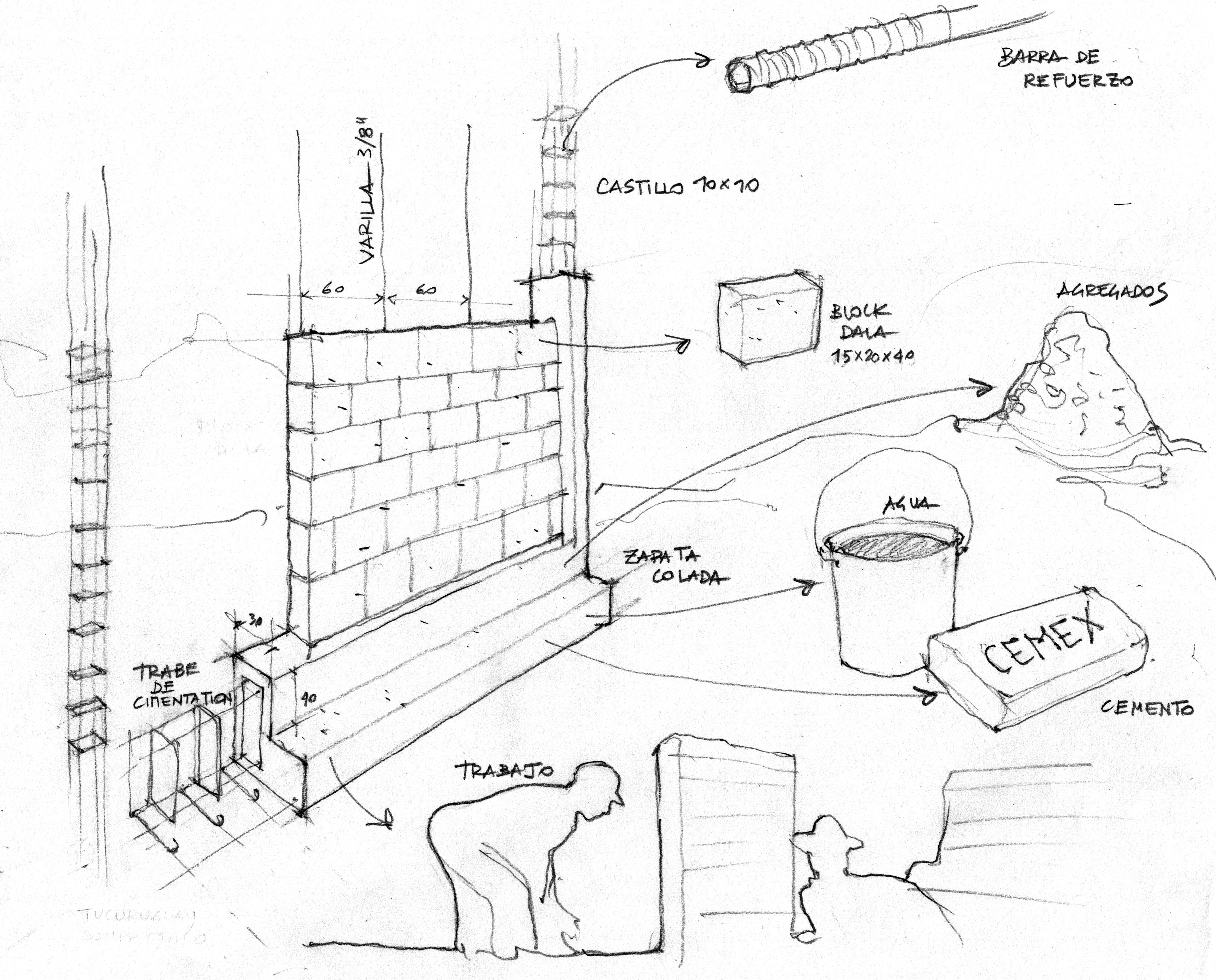

In this project I reflect on the political and cultural meanings of concrete as mixture of materials embedding organizational knowledge, economic resources, configurations of power, and modernist imaginaries of progress.

I am interested in concrete as entry point to technical-governmental assemblages that have informed the practice of autoconstruction in the peripheries of Mexico City. Part of this narrative will be the Mexican appropriation of and fascination for concrete as national material, a polvo magico to be transformed into several forms by architects as well as autoconstructors.

The supply chain of a concrete artifact in the periphery of Mexico City will serve as organizational device for my discourse. This supply chain will not be limited to the physical production and transformation of materials, but will also include political and cultural configurations that made that production possible. In so doing, I hope to destabilize the divisions between techno-material flows and political-cultural ones.

The narrative will at the same time unfold around different components of concrete (cement, water, aggregates, and iron bars); different sites of production, distribution, and consumption of materials; different histories (e.g.: from modernist imaginaries of progress, to the origin of informal settlements, to autoconstruction as techné and dwelling as a verb, to the geopolitics of concrete in Mexico City); and different encounters (e.g.: the organization of the autoconstruction site among peers, the involvement of families, and the network of shared technical knowledge and cultural practices on the ground).

The case study of my research is the periphery of Mexico City; more specifically, the informal settlements in Naucalpan (officially Naucalpan de Juárez), located in the northwest urban fringe of the city. These settlements have developed just at the boundaries between Naucalpan and Mexico City, along the Hondo River. The relevance of the location is at least threefold:

First, I am interested in the constellation of imaginaries around Naucalpan and the Ciudad Satélite project launched in 1957—Goeritz and Barragán’s Torres de Satélite (Satellite Towers) in the middle of the Periferico were the landmark of this new middle class suburban dream. I’ll reveal the shared modernist imaginaries around the use of concrete by both the middle and the low class in Naucalpan.

Second, in the Hidalgo neighborhood several stages of autoconstruction are still in progress—consider that squatters continue to invade vacant lots in Naucalpan, such as in the Los Remedios National Park.

Finally, in Naucalpan there are the three “typologies” of sites of production, distribution, and consumption of concrete that I am planning to visit:

– Cemex plant (e.g.: in 4A San Luis Tlatilco)

– Sites of distribution of construction materials (e.g.: 114 Metepec, Unidad San Esteban)

– Autoconstructed house (e.g.: Ignacio Allende and Prolongación 18 de Marzo)

In these sites I’ll try to interview respectively:

– Local sales/distribution representative of Cemex

– Owner of a construction material shop

– Autoconstructor

Naucalpan

Peso de Piedra

Compressive Strength of National Cementation and a Tensile Strength Experiment

by Diana Ruiz

This project seeks to render visible the “authoritarian narrative logic” of the Museo Nacional de Antropología through a resistant body enacting a cinematic choreography within the space. This project also searches for traces of labor that preserve and maintain the museum as a monolithic timeline of pre-Columbian Mexican history, and aims to weave these traces of institutional labor into the ‘alternative’ filmic experience of the museum.

Influenced by structuralist filmmaking and attendant to questions of the body’s interactions with artifacts, space, and concrete in the museum, this essay film takes a ‘visit’ through the museum as its premise. As the film and the visit unfold, encounters with museum personnel alter the pace and the tone of the experience. Here, I benefit from the concept of Dziga Vertov’s “kino-eye,” or cinema-eye, and films that explore architecture through formal interventions, such as Marie Menken’s Arabesque for Kenneth Anger (1961). In my gestural, at-times unorthodox movement through the exhibition halls, as well as concentration on light and shadows not meant to be contemplated in the same way as the artifacts themselves, I hope to evoke a meaningful engagement with the practices of the MNA’s idealization of museum spectatorship and, by extension, national subject-formation.

The other component of my film aims to formally represent museum labor as a constitutive element of the museum-going experience, and to interrogate the means by which (if at all) they are erased or hidden from view. I would like to briefly interview museum workers (janitors, ticket takers, security guards) and photograph them. Questions I am considering include: What is your favorite artifact in the museum and why? What role do you play in the visitor’s experience? Why is the museum important today? These portraits will be woven into the film, puncturing the diegesis in moments where the camerawork becomes entrancing and hypnotic. Firmly anti-ethnographic, my aim with these brief conversations is to rethink the possibility of the museum-going experience and posit another way to think about the ‘history’ and ‘work’ of the museum. I will take photographs with 35mm black and white film.

These two modes—defamiliarizing kino-eye choreography, and portraiture—take on questions of preservation, memory, space and the relationship between the museum and Mexico City.

Museo Nacional de Antropología